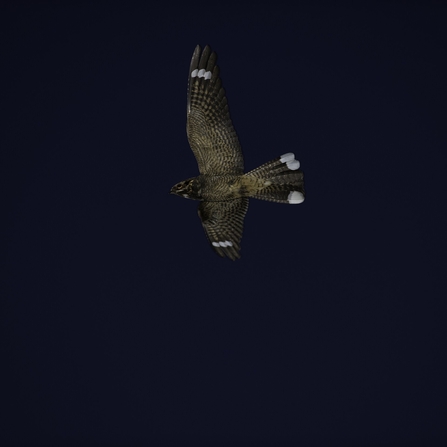

Male nightjar - David Tipling/2020VISION

Back in the 1950s when peat was still being cut by hand from the peatlands of Chat Moss in Greater Manchester, these rare birds would spend their days merrily ignoring the workers as they nested on the ground only a couple of metres away from them.

However, continued destruction of their habitat and landscape fragmentation caused breeding nightjars to become a thing of the past. Until this summer…

At first one of our intrepid birders wasn’t sure if they were hearing some form of malfunctioning machinery ringing out across the moss. But the distinctive churring sound of the nightjar quickly identified it.

Listen to the call of the nightjar below.