As part of our My Wild City project, The Wildlife Trust for Lancashire, Manchester and North Merseyside has been leading the development of a new Biodiversity Strategy and Action Plan for Manchester.

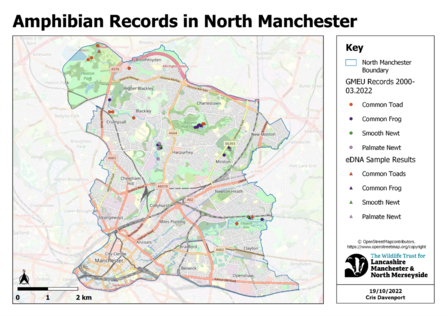

When developing this strategy with partners it became clear that species records for the city were limited in their number with those available often being old and likely out of date. For example, there were only eight records of toad species across the entire district of Manchester.

I was tasked with undertaking a new pilot in Manchester to look at the viability of using new science-based surveying techniques to address the gap in data associated with pond habitats.

Without accurate and up-to-date records of species populations, it is difficult to apply for funding and write management plans to maximise the conservation of parks and natural areas such as Local Nature Reserves (LNRs) and Sites of Biological Interest (SBIs).

Some species require specific habitats and management practices and not knowing which areas they inhabit may negatively affect the populations. Low records mean it’s also hard to track the spread of invasive species such as terrapins and mink which, without management, can do a lot of damage to the natural ecosystems.

Current species records for ponds in Manchester are mostly based on public sightings through citizen science and basic surveying techniques such as pond dipping which have their downfalls. Pond dipping can be very labour intensive as multiple long surveys need to be done on each site to properly capture as much data as possible, even then there are species that are unlikely to be caught because they are shy or stay away from the shallow pond edge. Especially for sensitive or protected species, such as great crested newts, pond dipping may also be damaging and invasive to the habitat, disturbing the silt and risking injuring the animals.